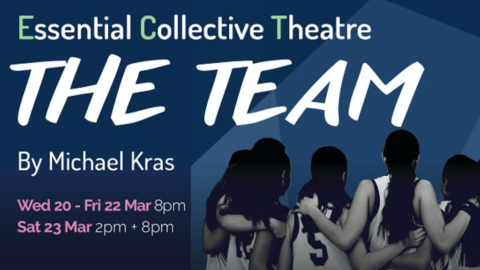

This year, our student embedders become one of The Team, as they follow the creation process of Essential Theatre Collective‘s upcoming show. To start, they...

Taming the Stage: Chris Abraham at Stratford Once More

Chris Abraham returns to Stratford’s Festival Theatre with another unique take on one of Shakespeare’s classics. After witnessing cross-gender casting and queer romances in Chris’ interpretation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream last year, I phoned him up to get the 411 on his new production of The Taming of the Shrew. Meanwhile, DARTCritic Elizabeth Amos is ahead of the game, and reviewed the production on its opening night. Check out Elizabeth’s review here.

Nick: Chris, you direct emerging work with your company Crow’s Theatre as well as Shakespeare at the Stratford Festival. Why do you think it’s important to return to classical playwrights such as Shakespeare?

Chris: I think in general when we think about classical work, and why we go back to classical work, is to understand more deeply the roots of the form. Why we go to back to Shakespeare in particular is because his grasp of human experience – mastery over the form if you will – is a particular achievement in his body of work. As a director these are iconic texts that the public have a relationship with. It is rare for the public now to have conscious and unconscious relationships with dramatic material. So one of the reasons it’s exiting to go back to Shakespeare is because you’re dealing with a playwright whose expression and body of work forms the tapestry of our culture in so many ways. You are tapping into people’s deep sense of identity, their humanity, intertwined with a writer. It’s powerful material to go back to.

A good example would be last year when I did A Midsummer Night’s Dream;, it’s a play that so many people know. Just the fact that there is a lot of knowledge of that play gave me a very unique opportunity to talk about love in a particular context.

Nick: Do you use the same tools as a director on both new work and your adaptations of Shakespeare’s work?

Chris: I wouldn’t say that my productions are adaptations. Although I would say A Midsummer Night’s Dream last year was a fairly aggressive conceptual proposition in relation to the play. I wouldn’t say it was an adaption though, simply because I changed a very small amount of the text and mostly did Shakespeare’s play. It was just the contextual device that reframed the situation of the themes in a particular way.

In terms of tools, the tools I use as a director are quite common. I spend a lot of time on a Shakespearean text or a new text doing a rough round of text analysis in which I try to identify the main idea that underpins the play. I break it down in terms of its parts to understand how the action of the play functions: how it functions on a moment by moment intention level for the actors, and how those intentions or desired outcomes argue for the main idea of the play. Maybe what’s distinct for me in terms of my approach, what I’ve learned in the last 10 years, is once I identify the main idea of the text I try to make sure that the idea is actually expressed in the results. That’s a fairly workman-like way of describing what I do. But I take a lot of pleasure in actually articulating what that idea is, then looking for ways, moment by moment, that express that position.

Nick: In playwriting or directing we are told to look for an issue at the heart of a text, and an insight into that issue.

Chris: Yes. Others might articulate it differently, but all good plays argue for a position on something. When I did Othello years ago, I felt that the play was arguing for the fact that love is stronger than doubts: love is more powerful than all of it, more powerful than anything else. Which is a bizarre thing to say about that play, because the antagonist is so strong. His [Iago’s] arguments for a cynical view of human nature are extremely persuasive, but I think ultimately Shakespeare’s point of view is that Desdemona stays; her unshakeable love for her husband transcends death, ultimately destroys Iago, and restores the audience’s faith in love as a redemptive force in the universe.

Nick: Without giving too much away, can you talk about why Stratford is producing The Taming of the Shrew, and why right now?

Chris: There is a very interesting investigation into the character of love and the appearance of love in the play. Secondly the difference between appearance and reality is a fundamental idea that Shakespeare is looking at in a lot of his plays. It’s big in Hamlet: his suspicion of surfaces and what lies underneath them. The character of love, and the truth of love versus the appearance of love, move through The Shrew in an interesting way. One thing I love to talk to the acting company about is, given how Petruchio’s behaviour to Kate might look to a contemporary audience – and even an early modern audience – challenges our capacity to see their relationship as a courtship. I believe it is a courtship and an expression of desire, and I do think Shakespeare is trying to articulate the uneasy birth of a romance between these two characters. That love story is contrasted by other romantic relationships in the play, which in my mind are more about surface, illusion, and the idea of love versus the reality of love. My production will argue for the birth of an uneasy partnership between two equal forces.

Nick: That’s a great teaser. Can we expect to see another “aggressive conceptual proposition” then, for The Shrew?

Chris: Haha. It’s interesting because I surprised myself with my reaction to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. [The production] was rooted in my feeling that the play is about the transformative power of love; transformative for individuals, society, and laws. That was at the centre of the play, and I felt I had to deliver on that in the production. So that is how I arrived at my approach. The right to love who we love is moving through the world and changing the way we think about love and sexuality and desire. I wanted to include some aspect of that fact in the production.

Now with The Shrew I feel it is a play that cannot be understood outside of an early modern context in terms of the forces that shape the behaviours and actions of the characters. If you move the play to a modern setting, there isn’t enough alignment between the predicaments of Kate as a character outside this slippery moment in history. In 1590 our notions about romantic love, marriage, and money were in transition and gender and power were transitioning as well. I think the play expresses that. When I contemplated moving it into a different time period, I felt like the problems are different for women in the 20th Century, the 19th Century, and the 18th Century then they were in 1590. I didn’t feel I could make a strong enough case in another period for the setting of the play. Given how challenging the subject matter is, it really requires me to look at the play in the context of the cultural conversation that was happening at the time.

Nick: Thanks Chris, I look forward to seeing the production on Friday, as do many Brock students.

Chris: That’s great to hear. Enjoy!

The Taming of the Shrew is playing at the Stratford Festival until October 10th.

Related Posts

It’s been over a week since Essential Collective Theatre’s world premiere of Our Lady of Delicias opened at the FirstOntario Performing Arts Centre and...

Emma McCormick and Kristina Ojaperv write,

As our journey into the evolving form of embedded criticism begins, we feel the title of Jordi Mand’s new work...

It’s been over a week since Essential Collective Theatre’s world premiere of Our Lady of Delicias opened at the FirstOntario Performing Arts Centre and...

Emma McCormick and Kristina Ojaperv write, As our journey into the evolving form of embedded criticism begins, we feel the title of Jordi Mand’s new work...

Leave a Reply (Cancel Reply)

Twitter Feed

Blogroll

DARTcritics.com is partially funded by the Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts, in support of student learning; experiential education; student professionalization; public engagement with the teaching, learning and production activities of the Department of Dramatic Arts; new ways of thinking; and the nurturing of links with our communities.