Frances Johnson graduated from the Department of Dramatic Arts in 2020 and was about to begin an internship at the Shaw Festival when the Covid-19 pandemic...

By Asenia Lyall

Every year the University of Windsor School of Dramatic Art produces multiple plays featuring its fourth-year students. This year, under the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, the department had to adapt. In collaboration with the Toronto theatre company Outside the March, the school commissioned playwrights and directors to create four plays entirely online, which were presented in a series called The Stream You Step In. The results were fascinating, varied and delightful. These are my observations of what worked about these innovative pieces of online theatre.

Because the plays were written with specific casts of university students in mind, the playwrights could write around the reality the actors are living in. Students who live together were written roles taking those circumstances into account. This makes the worlds of the plays feel realistic and offers possibilities for dynamic staging. It was exciting compared to some shows which are limited to talking heads in Zoom boxes.

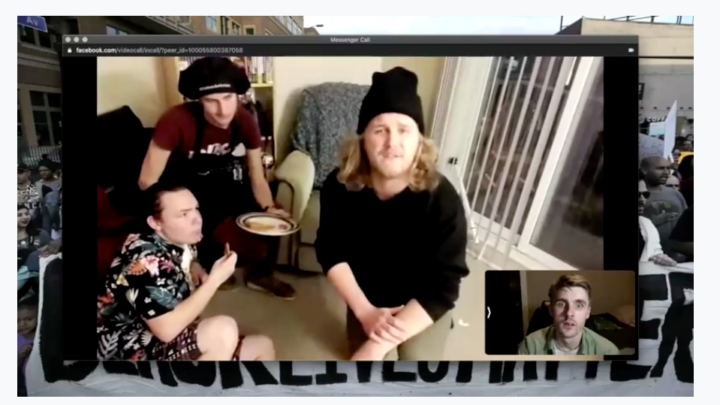

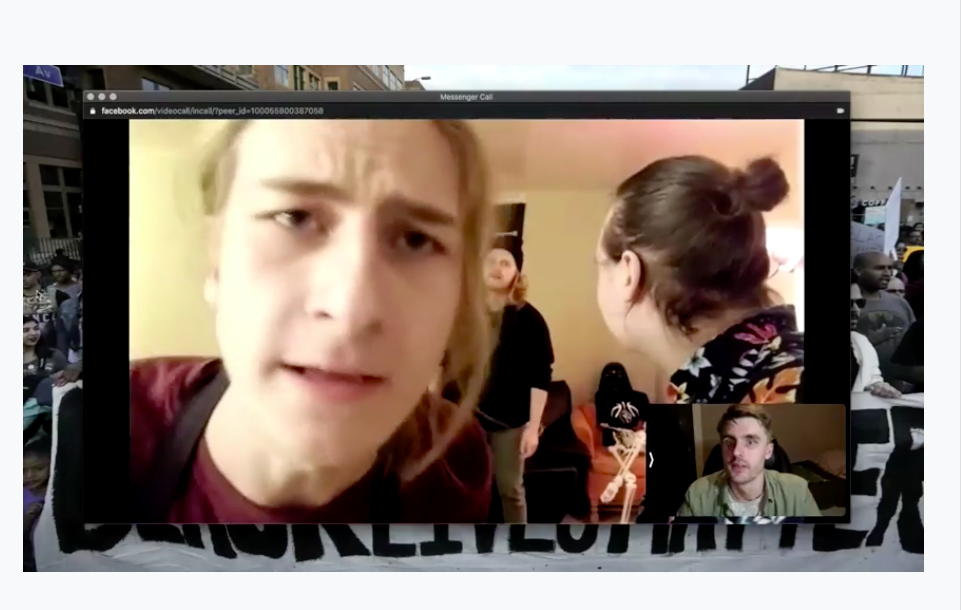

good white men written by David Yee, directed by Sébastien Heins and pictured above, opens with four friends playing video games. We are viewing Chad (Dustin Sedore)’s screen and hearing the voices of his friends cheerfully bantering. It’s lighthearted and naturalistic. “Performance will begin shortly” looms in the corner of the screen and I wonder, “is this the play?” After 20 minutes in the game “Among Us,” familiar to many young people who want a way to interact with friends without going near them, I realize that my instinct was right — this is simply a pre-show, and the play begins. I had certain expectations going into this show. Earlier that month I had watched the livestream of Yee’s Acts of Faith at Factory Theatre and after that brilliant online production I have a great deal of faith in this writer to adapt his scripts to suit the circumstances of the online world.

(left to right) Evander Jack Dewar, Dan Stanikowski, and Gareth Finnigan with Dustin Sedore in inset, in good white men. All photos in this story are screen grabs from recordings of these plays.

The subject of good white men is familiar to anyone actively engaged in current news and social media: activism and allyship. The idea that social media is the best way to change the world is a fast-spreading rhetoric among young people and the satirical picture that Yee paints of this world is funny, believable, and often frightening.

The audience views the play through Chad’s computer, on which he uses different chat functions to communicate, keeping us engaged with the changing digital landscape. The way the characters navigate the online world with the audience looking over their shoulder is realistic, detailed, and dynamic. Three of the characters come together in their living room and offer different camera angles for the viewer, one on Instagram Live and another through a Zoom call. The production embraces many possibilities of how to let the audience watch. We know exactly how we are situated because the cameras are built into the world of the play. It is truly an example of what Zoom plays should aspire to: It is written for the virtual platform but is in no way limited by it.

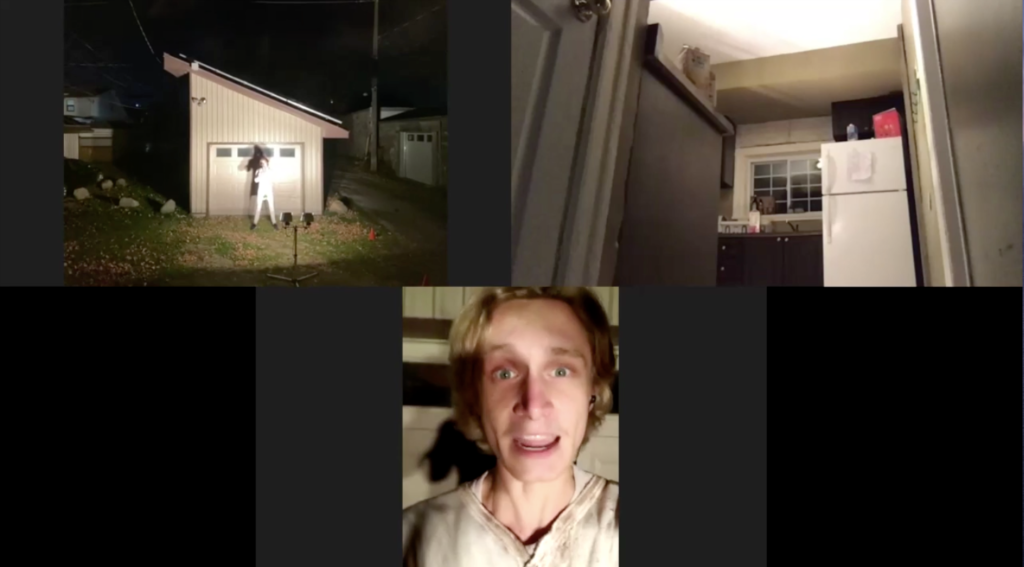

Karen Hines acknowledges the weirdness of Zoom theatre in a way that feels new, playful, and creative in The River of Forgetfulness or, Get Me Out of This Fucking Zoom Play. The script uses the reality we are all living in to fuel the fiction. Hines uses the circumstances of real online life to create an alien thriller drama. The moments that get messed up by Zoom are part of the world of the play, even when they are not. The show, directed by Griffin McInnes, plays with technical difficulty, and with three actors in one space uses three camera angles to create a dizzying, eerie world. It seems as though every creepy detail of Zoom calls is used — for example, how the lighting of a home when captured on camera can create black holes where eyes should be.

(left) Katelyn Doyle and Sam Cranston; (right) Alison Adams, Katelyn Doyle, and Sam Cranston in The River of Forgetfulness.

The sincerity of the acting lends itself beautifully to this piece: housemates Sam Cranston, Alison Adams, and Katelyn Doyle (pictured at the top of this story) perform brilliantly together. I felt as though I knew these characters, perhaps because I have been living the same horror of struggling through a performance degree online. The play is simultaneously a delightful escape from depressing reality as well as a compelling reflection of it.

The character of Caleb (played by Caleb Pauzé) fully utilizes the uncanny effect of particular connectivity issues to create a monstrous presence haunting the other characters. In a live production one simply cannot have an actor in two places at once. The virtual medium allows such effects, and this production embraces this. These creative uses of the medium are echoed in a line spoken by the characters, “please let our souls evolve as the drama evolves.” The audio and visual technical elements, coordinated by Dave Gauthier and Justin Yelle, take the world Hines has created and supports it brilliantly in this Blair Witch of online theatre production perfection.

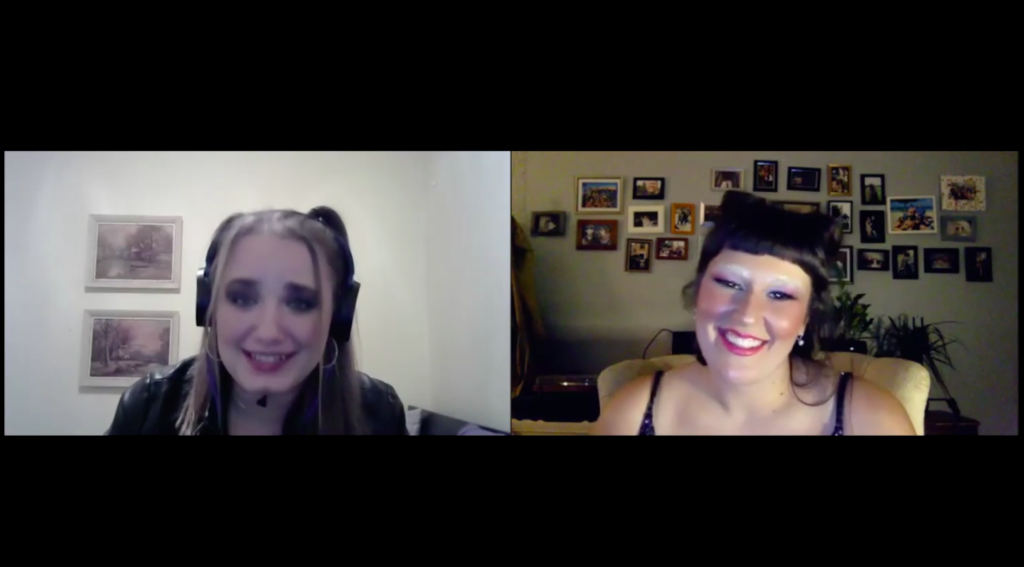

Elena Eli Belyea’s The Jubilant incorporates social media into the online theatre landscape. It is elevated with goofy filters and playful audience address through the character of Thistle (Bethany Joy Redford) on a YouTube live video. This is the only scene to take place over YouTube in the show; the rest take place on video call platforms. The pre-show layers in characters alongside what they’re watching on YouTube, allowing the viewer to get to know them before the play begins.

Jonnie Lombard and Marisssa Rasmussen in a scene from The Jubilant in which the camera functions as a fly on the wall.

This piece, directed by Kim McLeod, uses camera angles differently from good white men and The River of Forgetting. In both of those productions the cameras are phones or laptops that are part of the world of the play. In The Jubilant some cameras belong to the characters and others play the role of the fly-on-the-wall, inviting us into the lives of the characters when they understand that they aren’t being observed. A downside, alongside these dynamic choices, is that there are more moments of yelling than any of the other plays, which would not be a problem in live theatre, but I have noticed with online theatre, raised voices agonize the ears.

It was more difficult to identify the issues this play was addressing than in the first two shows; the subject matter ranged from isolation and relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic to the effect money has on art.

(clockwise from top left): Caitlin Jaisulaitis, Alannah Pedde, Elena Reyes, and Brennan Roberts in Thank You For Your Labour.

Thank You For Your Labour by Marcus Youssef is funny and tackles similar issues to good white men in a more naturalistic fashion. The characters are written, directed by Mitchell Cushman, and performed to come across like real young people. The production depicts the awkward, non-sensational parts of activism sincerely. The use of breakout rooms as a “choose your own adventure” moment is the most exciting and dynamic moment of the production. It highlights the charm and chemistry of Elena Reyes as Alicia and Alannah Pedde as Emily, whose well-written and performed flirtation is the central relationship in the story.

As these four uses of the same medium suggest, there are many different directions in which an online theatre production can go. There may be limitations in this time of isolation but in this case the limitations spark ingenuity and create stunning theatrical moments that delight and inspire. The Stream you Step In turned out to be a stream I didn’t want to step out of.

Related Posts

The Brock Dramatic Arts department’s fourth year students have been working hard on their final production of this academic year. Ouroboros is a piece of...

Rick Roberts’ Orestes, directed by Richard Rose, confronts the progressively blurring lines between real life and virtual life in a heightened version of the...

The Brock Dramatic Arts department’s fourth year students have been working hard on their final production of this academic year. Ouroboros is a piece of...

Rick Roberts’ Orestes, directed by Richard Rose, confronts the progressively blurring lines between real life and virtual life in a heightened version of the...

Leave a Reply (Cancel Reply)

Twitter Feed

Blogroll

DARTcritics.com is partially funded by the Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts, in support of student learning; experiential education; student professionalization; public engagement with the teaching, learning and production activities of the Department of Dramatic Arts; new ways of thinking; and the nurturing of links with our communities.