Hello theatre creators, educators, scholars and everything in between! I hope you’re having a productive-yet-restful summer. Ever wonder what it’s like...

Zoom vs. Everybody: New pathways in online theatre

By Holly Hebert

How do we keep theatre alive during a global pandemic? This question arose nearly a year ago, motivating theatremakers to develop Zoom theatre. Whether it be live or pre-recorded performances, it’s being done over Zoom. Since this exploration began, my work inside some such productions and my viewing of others has prompted me to wonder about the differing creative possibilities of this platform. As artists, are we in the midst of developing a Zoom theatre blueprint? Recently I saw Mount Allison University’s production of Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ Everybody, directed by Neil Silcox, and it brought a component to the blueprint that I had yet to experience: immersive theatre techniques. Immersivity within live productions usually brings an audience inside the show, directly addressing them and breaking the fourth wall completely. As with Brock University’s Scenes from an Execution and Concord Floral, in both of which I was involved, Mount Allison produces Everybody in a creatively challenging manner, inviting new elements of theatre into the world of Zoom.

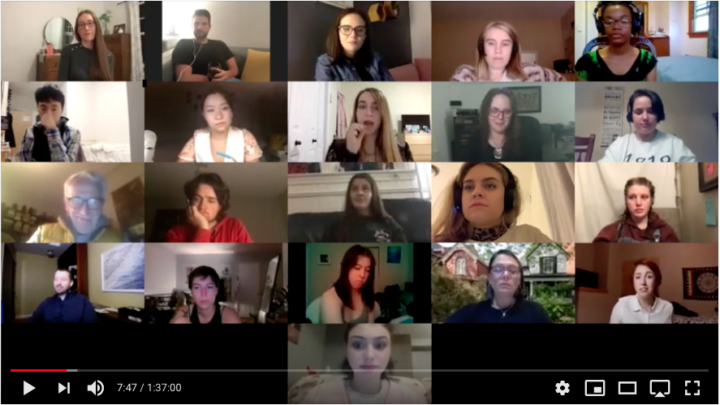

Everybody is a divinely written piece that makes death almost alluring, or, at the very least, peaceful. Jacobs-Jenkins’ script, based upon the fifteenth-century morality play Everyman, showcases an array of transcendental characters, offering a surprisingly relatable narrative given the unorthodox, dream-like world it evokes, and a randomized system as to what character each actor will play, determined mid-show (the script allows for this to be simulated, as was the case with the Mount Allison production). After presenting the ever-relevant characters of God and Death (Nathan Smith and Noemie Chiasson), the plot follows Everybody (Faith Higgins) – exactly the protagonist needed to connect a world of people. Everybody’s journey explores fear-incited greed and desperation, as they search for someone, anyone willing to die with them. Slowly, characters embodying other emotions and human needs emerge – this is where the immersion comes into play. Performing in isolation from their own bedrooms, many of these characters initially appear to be members of the Zoom audience (in the photo above, cast members are: Theresa MacAuley (top left), Danae Morrison (top right), Ryu Hiramoto (second row, first from left), Emma Yee (second row, second from left), Noémie Chiasson (second row, centre), Faith Higging (fourth row, centre), Aurora MacInnis (fourth row, far right), and Molly Dysart (bottom row, centre).

When logging on to Zoom for the show, audience members were given the option of leaving their camera on. This made for a fair amount of faces in Zoom’s gallery mode, many of which were not cast members. This was something I hadn’t yet experienced with the previous Zoom productions I’d seen, making my shock even greater when characters began appearing from the audience. However, when there are so many on-screen boxes, it makes tunnel vision on performers quite difficult, whereas a brightly-lit stage consistently pulls focus in the right direction. The attempt at audience immersion as performers were revealed amongst them was a fun surprise and, given the dialogue between cast and spectator that happens in the script, it’s a natural decision to have the audience seen onscreen. The intent behind this was smart; however, my tendency to gravitate towards the fine details in acting when watching any show made this choice somewhat distracting for me. But that’s the kicker when dealing with a new form of theatre: you don’t know what will and won’t work until it’s tried, both as an artist and audience member. It’s now evident to me that my preference lies in simply seeing actors clearly, and once scenes began to appear that showcased only them, my attention was tripled. The far more detailed characterization and moments of isolation became notable, piquing my engagement.

Soundwaves of characters’ voices in Everybody. the image is a screen grab of the Mount Allison production.

My intrigue was furthered once again when, ironically, no person was seen onstage. For a few moments the dream-like states were paused, and an audience simply listened to the characters speak, viewing only the soundwaves of their voices. It felt as though I was eavesdropping on an intimate conversation between friends. And I believe that is something particular to Zoom theatre. Watching these flashes of faceless scenes by myself had a very personal effect. Had I been sitting with a full audience of people listening to actors speaking against an empty stage, my reaction would be entirely different. Rather than feeling as though my device is a source of privacy for myself and the performers, I would feel like one anonymous viewer amongst the mass of listeners.

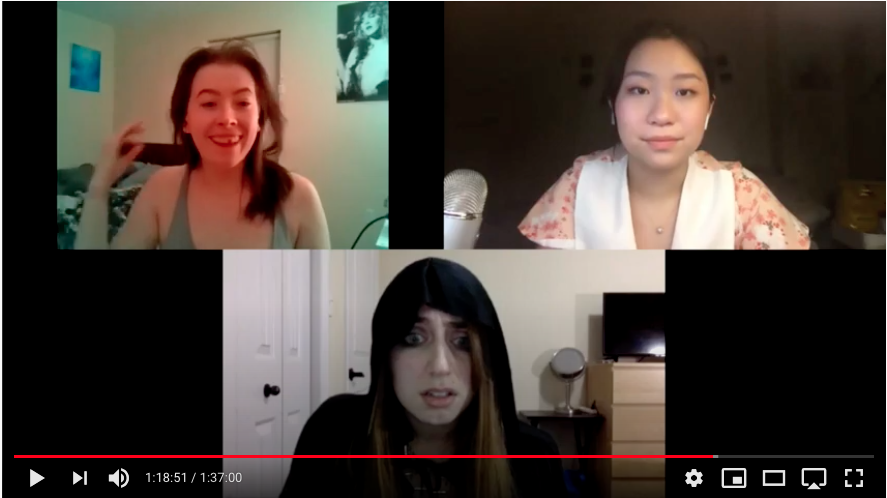

Faith Higging (top left) as Everybody, Emma Yee (top right) as Love, and Noémie Chiasson (bottom) as Death in Everybody. The image is a screen grab from the Mount Allison production.

Having been a part of Scenes from an Execution and Concord Floral within the last few months myself, I’ve been somewhat of a guinea pig to the pros, cons, and experimental steps in creating this kind of theatre. Advantages to using Zoom as a theatrical mode may be considered scarce compared to what have become clear as the many advantages of in-person theatre. Bodies simply being in a space together, whether it be a cast of actors or a whole production team, has become a blessing to never take for granted rather than an expectation. Rehearsing through a screen instead of in a studio is just one example of the challenges of Zoom theatre. However, when considering those who may not have previously had the opportunity to see in-person theatre, or been able to see friends and family performing when they’re in other parts of the world, Zoom theatre proves to be advantageous.

As artists began to work through the successes and challenges of Zoom theatre, more questions started to come up, beyond the initial worry about keeping theatre alive in the first place. One such question is pre-recording. The central debate around this is whether its lack of liveness can still allow it to be considered theatre. Mount Allison undertook a phenomenal task, as they performed their production live. This does limit some theatrical elements: with each actor performing alone in their own living space, production responsibilities that would usually be taken on by a team inside the theatre now fall to the actor. Given that it’s very difficult for a person to perform, act as their own stagehand, and handle their own lighting at once, Mount Allison’s production did lack some technical elements. Despite this small weakness, live performance offers the mutual connection between audience and creative team with the knowledge they are sharing an experience together – something Mount Allison exemplified exceptionally well.

Having had such experiences from an actor’s perspective in Scenes from an Execution and now as an audience member, I’ve found that no matter which side of the screen I’m on in a Zoom theatre experience, there’s an energy reminiscent of face-to-face theatre activity. It takes an honest love for the arts to perform on Zoom with the momentum one would usually have performing for an audience in a theatre. We are aware that spectators now have endless distractions at their disposal. They could have their entire focus on the show, or they could be using it as background noise while they cook dinner. As a performer, this could easily be seen as a negative, but can also be viewed as a challenge to work on keeping the audience’s focus – asking what can be done so they never want to look away from their screen. This perspective heightened my energy massively when performing. Now as an audience member, I give my full attention, hoping to receive the energy that makes me never want to look away. It’s that energy that brings nostalgia.

Although what I’ve just described concerned live Zoom theatre, such energy can still be present if the production is pre-recorded. While the shared experience element is not there, pre-recording allows for many additional components. There’s time to pause between filming scenes for set, lighting, and costume changes, as well as editing to make for smooth scene transitions and the capacity to add in sound cues. This was the route Concord Floral took, and it did offer a great amount of freedom around production elements. For some people, though, these points reinforce the argument that a pre-recorded Zoom production is not theatre. However, I’d rebut that theatre was always developing new forms of creativity even before it was moved into Zoom. Using pre-recording to incorporate more lighting and sound can enhance a theatricalexperience. To complicate the debate around pre-recording further, some would simply state that through the use of a screen, theatre is dismantled. That would then negate live Zoom theatre as well. It’s a complex dispute, but I currently see Zoom theatre is in an invention process, which is partly why the questions and discussions surrounding it are growing but also why there’s no confirmed answers.

Zoom theatre remains a work in progress, meaning there’s a lot of creative freedom as artists experiment. This development stage, full of triumphs and defeats, could be a meaningless task to pass time during the pandemic. Or, it could become the building blocks to stimulating revelations. Mount Allison’s production of Everybody brings fresh techniques to theatre at this particular moment, exploring what Zoom can contribute to a live show. And as they take this brave step, we, as theatre makers and theatre lovers need to recognize these efforts. To discourage or negate any creation someone is producing – from theatre to poetry to sculpture and everything in between – would be, dare I say, a crime to art at the moment. I’m a strong believer that theatre is an outlet and a connector formany, shining light on whatever an artist desires. It can be an emotional release for some and eye opening for others. And during a pivotal time in society such as now, creation can be what gives many hope.

Related Posts

For nearly two years, theatre lovers have felt entrapped in their own little purgatories. Artists have been unable to perform on stages, and audiences been...

Frances Johnson graduated from the Department of Dramatic Arts in 2020 and was about to begin an internship at the Shaw Festival when the Covid-19 pandemic...

For nearly two years, theatre lovers have felt entrapped in their own little purgatories. Artists have been unable to perform on stages, and audiences been...

Frances Johnson graduated from the Department of Dramatic Arts in 2020 and was about to begin an internship at the Shaw Festival when the Covid-19 pandemic...

Leave a Reply (Cancel Reply)

Twitter Feed

Blogroll

DARTcritics.com is partially funded by the Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts, in support of student learning; experiential education; student professionalization; public engagement with the teaching, learning and production activities of the Department of Dramatic Arts; new ways of thinking; and the nurturing of links with our communities.