“The magic of theatre” – a common descriptor of productions and a personal favourite explanation as to why I love the arts. Theatre has an ability to...

A new take, and a call to action: Watching Glory Die at the Grand Canyon theatre

By Mae Smith

Watching Glory Die is a call to action. Judith Thompson’s play is based on the true events surrounding the death of Ashley Smith, a teenage inmate at Kitchener’s Grand Valley Institution. If you’ve heard of the tragic story, you’ll know that after an exceedingly long period in solitary confinement, Smith strangled herself in her cell while under suicide watch. The incident raised many questions about the treatment of inmates in Canadian prisons and director Kendra Jones’s take on the work further amplifies them.

The play is structured by three characters’ monologues: the inmate Glory; her mother Rosellen; and the correctional officer (C.O.) who saw everything, Gail. In contrast to the play’s world premiere in 2014 where all the characters were played by one actor (Judith Thompson herself), Jones employs three powerful actors to unwind the twisted story into three perspectives. Each speaker passionately urges the audience that their perspective is the truth.

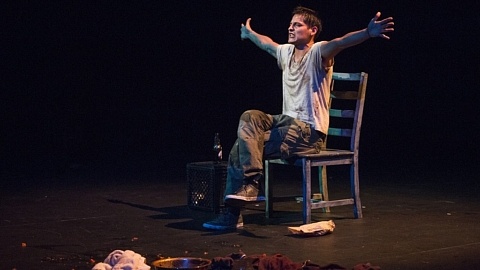

The lighting design (Sebastian Quinn Hoodless) sticks mostly to soft spotlights, creating an isolated confessional-like feel. This isolation is accentuated further by the lack of set save for a stage-length silk and a chair, both of which are used infrequently.

Although not a characteristic unique to the Grand Canyon theatre, the sound of Toronto outside unfortunately drowned out the sound design (John Norman) in the small garage-turned-black-box theatre the night I saw the show. It became unclear whether I was hearing purposeful ambience or just life happening outside.

The overall minimal design and intimacy of the space compels the audience to focus on the characters’ defenses – and they do feel like defenses. Rosellen (Jennifer McEwen) turns and speaks facing a wall at times, suggesting a larger audience than just us in the theatre. Later, her final lines are reminiscent of a closing statement in a trial directed to a jury. Gail (Pip Dwyer) frequently speaks as if trying to prove her innocence although it feels less like testimony. To whom Glory is meant to be speaking to is often less clear.

When we meet Glory (Kaitlin Race) she is floating between the harsh reality of the prison and a fantasy she reverts to in order to avoid the pain of it. The C.O.s punish her frequently for off-hand comments or for defending herself. She’s looking at me funny so she must want to kill me – charge her. She can’t just be holding a tampon in the shower, it’s a knife – taze her. She’s begging me not to choke her out but she’s screaming so I feel threatened – charge her. (Race’s physicality is impressive as she tousles with the silk as if it’s an attacking C.O.). She’s suffocating herself regularly, she wants attention – not help – wait until she stops breathing next time to teach her a lesson.

At top: Pip Dwyer, Kaitlin Race, and Jennifer McEwen in Watching Glory Die. Above: Kaitlin Race. Photos by John Gundy.

Gail recounts the time leading up to Glory’s death, reflecting an inner conflict as she rationalizes her own involvement in the events leading up to it. Dwyer skillfully wavers between a defensive façade of authority and the guilt Gail knows she should feel. In order to keep her power and do the only job she knows she must keep the inmates down. She must blame them for getting here and blame them for not taking it on the chin.

Rosellen offers the opposite view, pleading for her audience to understand the humanity in her 19 year-old adopted daughter who is now in the fifth year of a six month sentence. Glory is not just some teenager making trouble like her birth mother, a girl messing around with boys in barns, as Rosellen describes. She believes Glory made a simple mistake as a kid and doesn’t deserve the time she’s been in prison. Not that this isn’t true, but this apathy towards those in trouble outside one’s inner circle allows injustice to keep happening until it hits close to home.

Suppressing her sympathy in a similar way, Gail justifies her behavior towards the inmates and her strict adherence to orders despite how they clash with how she feels. When she’s confronted with the consequences of her actions, she insists she should be able to live a normal life and move on from the mistake. Dwyer literally backs herself into the corner, shrinking from her previous position held largely upstage before her light fades out.

It is a familiar pattern to see the victim turned perceived aggressor for reacting to injustice, especially considering recent events regarding protests in solidary with Wet’suwet’en peoples. Jones even makes a point of pointing out the disproportionate antagonism towards justice for Indigenous peoples in her director’s notes.

When the cast breaks the fourth wall, the audience becomes complicit in the act and are implored to right the wrong we have seen. That night, we watched Glory die. She wasn’t the first but the play would want her to be the last.

Watching Glory Die, produced by LOVE2 Theatre Co. in association with impel Theatre, continues at the Grand Canyon, 2 Osler St., Toronto through February 29.

Mae Smith is a Brock University and DARTcritic alumna currently working as the Associate Editor for Intermission Magazine.

Related Posts

Sometimes, what you really need is to see grown adults dressed as turkeys dancing with pilgrims. It’s good for the soul. As is the rest of Holiday Inn – a...

If you love your theatre dark, shocking, and emotionally raw, but still want to have the occasional laugh, then Cliff Cardinal’s Huff is for you. Be aware...

Sometimes, what you really need is to see grown adults dressed as turkeys dancing with pilgrims. It’s good for the soul. As is the rest of Holiday Inn – a...

If you love your theatre dark, shocking, and emotionally raw, but still want to have the occasional laugh, then Cliff Cardinal’s Huff is for you. Be aware...

Leave a Reply (Cancel Reply)

Twitter Feed

Blogroll

DARTcritics.com is partially funded by the Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts, in support of student learning; experiential education; student professionalization; public engagement with the teaching, learning and production activities of the Department of Dramatic Arts; new ways of thinking; and the nurturing of links with our communities.