Rick Roberts’ Orestes, directed by Richard Rose, confronts the progressively blurring lines between real life and virtual life in a heightened version of the...

Jem Rolls Is a Gem: “The Inventor of All Things” at FringeTO

A note from Hayley:

We have a new face at DARTcritics! Evan Bawtinheimer is a recent graduate of the Dramatic Arts Department at Brock University, and an avid theatre goer (if you live in Toronto and dig theatre, then you’ve probably seen him and heard his laugh). Evan is in the interesting position of a) being a DART alumnus, b) being heavily entrenched in the Toronto theatre community, and c) being an excellent writer. He approached us about contributing to the site during FringeTO season, and we were thrilled to have him.

Keeping in kind with the #FringeFemmeTO movement (a hashtag started by Fringe artist Sophia Fabiili which you can catch up on here), Evan has added a Bechdel Test to the end of each review. While the Bechdel Test is not a judge of the artistic value of a piece, it works as a kind of feminist accountability system.

Welcome, Evan, we’re glad to have you!

(AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION: Read this critique as you normally would and, on occasion, try reading the words by moving only your head. Stop when you get dizzy. Repeat as needed. This feeling simulates being in a Jem Rolls audience—in a good way.)

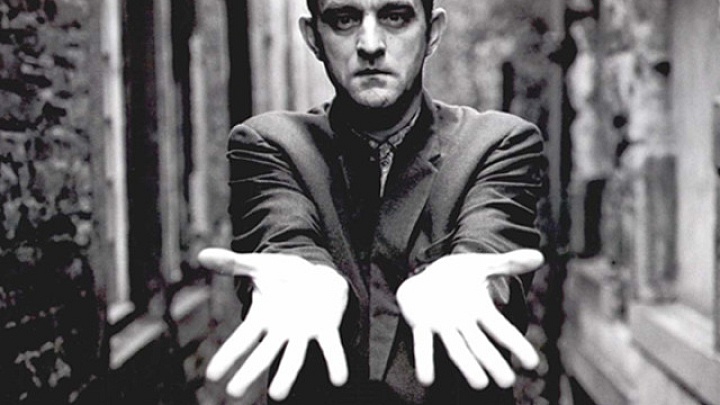

Jem Rolls is the story teller we all wish we could be. He is well-informed, sincere, and most importantly very enthusiastic about his story. The Inventor of All Things (which is not listed in the Fringe program!) tells the story of Leo Szilard: a man you have never heard of before, but whom Rolls argues should be recognized as a hero.

During the Second World War physicist Szilard is struck with an epiphany regarding nuclear fission: he realizes its potential as a new energy resource for the world and as a powerful weapon for German scientists, and develops his idea further under immense secrecy. The story spans several years as Szilard encounters many well-known names, including various Presidents, Albert Einstein, and J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Let’s talk story-telling. This is a different type of solo performance. This is not a Daniel MacIvor solo show. This is story telling. Rolls isn’t portraying any characters or having any lengthy dialogues, instead he relies on his own skills as a story-teller and the facts of Szilard’s biography. Similar to gathering around a campfire and hearing ghost stories, Rolls uses only his words (and a few well deserved spotlights and sound cues) to get his story across, but the words are his spectacle. If another performer replaced him, I have a feeling the show wouldn’t work; without Jem there is no show. Plus, the story is funny. In both wit and tone, Jem makes what could have been a bland history lesson accessible and fun.

The story lulls around the last fifteen minutes. By this point, there are far too many names, dates, places, and conflicts to remember all at once. Plus, there are virtually no female characters in the show. Some are present – Eleanor Roosevelt is mentioned by name – but her role in the story is minimal, if unnecessary. I don’t fault Rolls for this; it’s not surprising that science was a heavily patriarchal field of study in the 1930s, just as it is now (re: Nobel Laureate Tim Hunt and his science “girls”). The role of female scientists were, and still are, simply not as recorded as their male associates.

There aren’t many Canadian plays set during the First and Second World Wars (I’m kidding. There are billions). There are few shows that simply tell a story without adding artificial theatricality and pretend dialogue, however. The Inventor of All Things doesn’t preach ethics on war or talk down to us with a moral solution. It ends on a very graceful note, elegantly wrapping up the story.

The Bechdel Test:

(1) it has to have at least two women in it – NO

(2) who talk to each other – NO

(3) about something besides a man – NO

The Inventor Of All Things DOES NOT PASS the Bechdel Test.

Related Posts

Every year the University of Windsor School of Dramatic Art produces multiple plays featuring its fourth-year students. This year, under the circumstances of...

Pre-recorded digital theatre can reduce performers to ghosts. The moment of ephemerality has passed; a recording hopes to capture its spirit for the viewer. I...

Every year the University of Windsor School of Dramatic Art produces multiple plays featuring its fourth-year students. This year, under the circumstances of...

Pre-recorded digital theatre can reduce performers to ghosts. The moment of ephemerality has passed; a recording hopes to capture its spirit for the viewer. I...

Leave a Reply (Cancel Reply)

Twitter Feed

Blogroll

DARTcritics.com is partially funded by the Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts, in support of student learning; experiential education; student professionalization; public engagement with the teaching, learning and production activities of the Department of Dramatic Arts; new ways of thinking; and the nurturing of links with our communities.