For nearly two years, theatre lovers have felt entrapped in their own little purgatories. Artists have been unable to perform on stages, and audiences been...

The After Year Reaches London Fringe

Critic in Residence Nicholas Leno writes,

The apocalypse has reached London, not 28 days later, but right now! Last week St Catharines’ Dragonfire Players were in London, Ontario performing their newest show The After Year for the London Fringe Festival. I began following Dragonfire Players in April when Hayley Malouin and I interviewed the show’s creators, Tanisha Minson and Anna MacAlpine, about their process. Hayley and I wanted to highlight the work of local artists in our community as part of our coverage for St. Catharines’ annual arts festival In The Soil.

There is a lot I have to say about this production, but I feel it is important to begin by saying that The After Year offers a unique insight into the post-apocalypse genre. Its characters’ use of art to preserve their humanity and survive under the most difficult conditions is a concept that I find not only interesting but inspiring. The group tackled a lot of issues, from over-population to the representation of transgender characters, which may have been a little over-ambitious. But the question “What is art now that the world has ended?” that MacAlpine asked me at our interview in April was definitely addressed when I attended The After Year last Thursday night. More on that to come.

First, for those of you who missed In The Soil and our coverage of it (pause for a brief moment of shame) a quick recap: This show originated as a collective idea between Dragonfire Players’ MacAlpine and Minson, who then assembled a team of Brock alumni and students. The group decided to forego the role of a director and approach the production as a collaborative team. Their shared education meant a mutual vocabulary of terms and techniques as well as an atmosphere of familiarity that made it easy to foster an ensemble who could freely exchange ideas and direct each other. The script originated in the hands of company member MacAlpine who drafted the script and performed rewrites alone, but always took feedback and discoveries the company made with her to the editing table. Want to know more about Dragonfire Players’ creative process? Check out my preview article here.

After a brief run at In The Soil, the production received a wide range of responses. To follow up, Minson invited Hayley and me for coffee to discuss the feedback the company received. A lot of our discussion was based around story construction. We all agreed that The After Year at In The Soil lacked a central character, a protagonist who we could identify with. Science fiction stories that the company was working from usually contain a hero who embarks on a quest, and this seemed to be missing. More information on the details of our post-show discussion can be found here. The After Year closed at In The Soil on April 26th and was scheduled to open at London Fringe on June 5th, giving Dragonfire Players just over a month to rewrite their script on top of training Geoffrey Heaney to replace Dylan Mawson in the role of Nathaniel West. Although Minson articulated how large and daunting their task over the next month was, she still seemed excited to return to the rehearsal hall and to continue polishing their creation. So, with much anticipation I waited over the next month to see what the production would become.

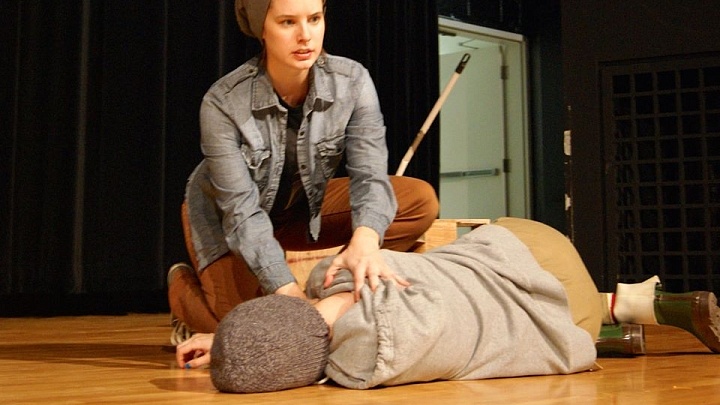

I caught up with Dragonfire Players last Thursday during their final rehearsal before opening later that evening (my relationship with lighting designer Nicole Titus, as well as my friendship with many of the company members, was partially my reason for attendance). The group was under some serious time constraints – festival rules only permitted them two hours of rehearsal in their new space at the London Convention Centre. This theatre was newly added to London Fringe’s list of venues since dropping Fanshawe College Theatre in Citiplaza last year. Its proscenium configuration is considerably different than the black box style of the Sullivan Mahoney Courthouse Theatre where the show played at In The Soil. The After Year is set in the violent and dangerous world of an apocalypse, meaning a lot of intense combat choreography. I’m not just talking about a few stage slaps: knifes, baseball bats, and a broom are only a few of the makeshift weapons we see in this ferocious tale. A new stage meant that the portion of the rehearsal not spent rehearing technical cues was devoted to rehearsing and rearranging the fight scenes.

After witnessing a rehearsal and later that evening a performance, it was clear that a lot about The After Year had changed. In fact it was a completely different show. Rewrites of the script focus much more of the narrative’s action around Jackson, showing the ways in which his choices affect the lives of others around him and ultimately even the world itself. Jackson’s hero quest begins at about twenty minutes into the story when a genetically modified woman attacks the group’s camp (which felt late for a 55 minute show). Much to Jackson’s surprise this GeneMod is infected with the deadly sleeping virus, a shocking discovery that makes Jackson question his family’s immunity and ultimately their ability to survive. We learn more about Jackson as he attempts to solve this mystery, including his involvement in the virus’ creation.

Eventually Jackson is faced with a final choice – we reach that climatic moment of the quest where the hero risks everything. The result is devastating. The ending slapped me across the face, and I can say without a doubt the story has become a lot more suspenseful since it premiered at In The Soil. However, I feel the ending would have had an even greater impact if the sense of family between the characters was greater. At times it is unclear if the characters even enjoy each others’ company because so much of the dialogue is centered on their disagreements. Jackson’s quest appears to be about saving his family, which means the audience needs to care as much about Jackson’s family as he does. If we did, the ending would have as great an impact on us as it does Jackson.

Despite scenes of combat that left many audience members cringing for the characters in pain, I found the play’s most interesting moments to be Jackson’s retreat into his imagination. Jackson is a genetically modified super-genius, but dons a grey trenchcoat and fake accent to play pretend with a teenager. It’s not just the irony and fun British accents that get me here, it’s the insight these scenes provide into our world. The group reminds us that humanity cannot survive through brute force and violence alone; we must create stories as a way to cope with and understand our existence. Zombie and end-of-the-world tales typically feature heroes who survive thanks to a combination of intellectual and physical abilities, but our hero’s survival seems to be in part credited to imagination.

As I mentioned above, the concept of art and our imagination as a tool for survival is important to creators MacAlpine and Minson. However, I feel this insight has gotten somewhat lost within the many issues this production attempts to pursue. The story is set in a dystopian world filled with genetically modified humans and a government that uses an epidemic to eliminate some citizens for the betterment of society. This already evokes a wide range of philosophical, ethical, and political debates. Then the audience learns that their hero is transgendered; however, instead of this being a straightforward character choice (as with the character Sophia in the popular Netflix series Orange is the New Black) the company also seems to want to start a conversation about the politics of being transgendered. All of this is a lot for any audience to take on board in 55 minutes. While I appreciate the ways in which the company tried to make their story relevant, I feel that all these issues combined with a new method of creation overwhelmed the production and ultimately its audience.

If Dragonfire Players continue to develop this story (which I feel they should), I recommend they revisit the make-believe scenes between Jackson and Phoenix. These moments where we see Jackson’s imagination come to life are pleasurable for us for the same reason they’re pleasurable to Jackson: they offer a break from the play’s dominant mode of realism. The audience literally gets to escape with the characters into another reality, which is why these two brief scenes make for good theatre. I encourage the company to ask themselves why they chose to tell this story onstage, and what the theatre has to offer a post-apocalypse story that other mediums cannot. If the play’s insight lies in the way in which imagination and story offer us an escape from reality and preserve our humanity, is there not a way for us see this more onstage? Can the audience be let into the characters’ imaginations to see Nathaniel’s relationship with Shakespeare, Phoenix’s relationship with the rock group Queen, and Athena’s relationship with books? While violence and fight scenes can be entertaining, I can’t help but wonder if that kind of action is better suited for special effects in film, while the investigation into the character’s imagination seems more suitable for the theatre.

The After Year has transformed since premiering at In The Soil only one month ago, in many ways for the better. And what has not changed is the group’s positive attitude and love for their creation: this is as strong as the first time we met in April. It is my hope that The After Year continues to develop after its run at London Fringe. The company is excellent at accepting and negotiating feedback, a mark of true professionalism that has definitely assisted them in growing their creation. It’s fantastic to see a group of young artists coming together to create work that they find interesting and thought-provoking. To Dragonfire Players: congratulations on the second run of your production. I hope to see you continue to develop your wonderfully entertaining post-apocalyptic stories and I hope my writing has assisted your company and this show in its growth. You’ve shown us that, with or without a George Romero (those of you not up on zombie references, click here), it’s a good imagination that makes good theatre.

Related Posts

It’s been a few weeks since the final performance of Brock University Department of Dramatic Arts’ Fall Mainstage, Scenes from an Execution. Closing off their...

Here’s Holly Hebert’s final solo vlog from behind the scenes of the Fall 2020 DART Mainstage, Scenes from an Execution. She and Asenia will round off this...

It’s been a few weeks since the final performance of Brock University Department of Dramatic Arts’ Fall Mainstage, Scenes from an Execution. Closing off their...

Here’s Holly Hebert’s final solo vlog from behind the scenes of the Fall 2020 DART Mainstage, Scenes from an Execution. She and Asenia will round off this...

Leave a Reply (Cancel Reply)

Twitter Feed

Blogroll

DARTcritics.com is partially funded by the Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts, in support of student learning; experiential education; student professionalization; public engagement with the teaching, learning and production activities of the Department of Dramatic Arts; new ways of thinking; and the nurturing of links with our communities.